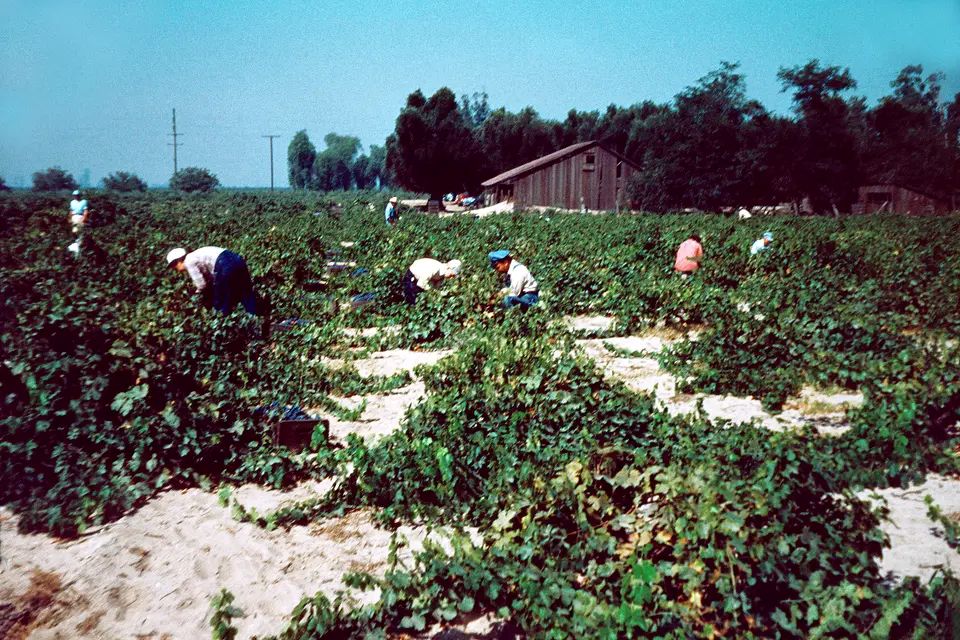

Lopez Ranch, the largest extant vineyard in the Cucamonga Valley, was planted in 1919. Like many Cucamonga vineyards before it, it is slated for development. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

RANCHO CUCAMONGA, San Bernardino County — Angela Osborne couldn’t find the vineyard she was searching for. The winemaker had heard about Hofer Ranch, one of the last holdouts of the wine scene in the Cucamonga Valley — a region about 40 miles east of Los Angeles that had once been blanketed in grapes but whose vineyards had all but disappeared.

She knew it had 10 acres of nearly century-old Grenache — the specialty of her label, A Tribute to Grace Wine Co. But locating Hofer Ranch was tricky. It wasn’t on Google maps, and she couldn’t get a phone number for Paul Hofer III, the fifth-generation owner.

Eventually she found an approximate location on a California history website. In the spring of 2014, with a not-quite-1-year-old baby in the back seat, Osborne drove south from Santa Barbara.

When she found herself on a five-lane thoroughfare sandwiched between UPS’ regional air hub and the Ontario International Airport, she was sure she was lost. Then she saw the old stone wall and a plaque announcing “ESTABLISHED 1882.” Passing through the ranch’s wrought-iron gates, she was mesmerized by the oasis: a lush jungle of old-grove eucalyptus, palm trees, cacti and creeping bougainvillea. The Hofer Ranch Grenache was like nothing Osborne had seen before, the vines so hulking that they resembled trees, throwing asymmetrical shadows over the sandy loam soil.

Left: Hofer Ranch once contained about 920 acres of wine grapes. Today it has 10. Right: Just-harvested Palomino grapes at Lopez Ranch on Aug. 13, 2024. Photos by Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

Left: Hofer Ranch once contained about 920 acres of wine grapes. Today it has 10. Right: Just-harvested Palomino grapes at Lopez Ranch on Aug. 13, 2024. Photos by Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

“We took the grapes that year, and it was quite evident that we’d found something really magical,” Osborne says.

A decade later, her Hofer Grenache is the most in-demand wine at her tasting room. “Every week there’s someone who comes in and asks us if we’ve got any Hofer,” Osborne says.

Osborne isn’t the only California vintner lately enamored with the Cucamonga Valley. A cadre of high-profile winemakers including Raj Parr (Scythian Wine Co.), Abe Schoener (Los Angeles River Wine Co.) and Mikey Giugni (Scar of the Sea) have flocked here in search of what fruit remains, transforming what looked like an enervated wine region into an ultimate cool-kids destination.

Cucamonga Valley American Viticultural Area

Map: Nami Sumida/S.F. Chronicle

Most of these winemakers buy grapes from Lopez Ranch, the largest extant vineyard in the Cucamonga Valley at over 300 acres. The 106-year-old Zinfandel and Palomino vines here, each one a floppy little bush, are whipped by a powerful breeze, accentuated by the whir of Interstates 15 and 210 nearby. Framing the view are the green San Gabriel Mountains, with the snow-capped Mount Baldy, and a Target.

Lopez Zinfandel “is regularly the most shockingly high-quality fruit that we work with anywhere,” says Garrett York, co-owner of Herrmann York Wine.

But at the same time that Lopez’s star is rising, its end is also in sight. The plastics manufacturer Intex Properties now owns the land and will turn it into a logistics hub. The timeline is unclear; each year, the winemakers wonder whether this Lopez harvest will be their last.

“It will be developed,” says Domenic Galleano, whose family has farmed Lopez for over 40 years. “It’s just a matter of when.”

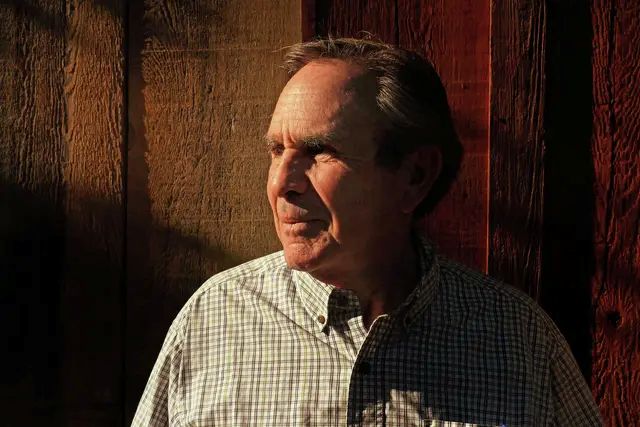

Fourth-generation vintner Domenic Galleano at Galleano Winery, where the redwood wine tanks date to the late ’40s and early ’50s. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

Its plight is emblematic of the Cucamonga Valley as a whole, where for the past half-century development has encroached on vineyards to the point where it’s almost extinguished them — almost.

A century ago, a bird’s-eye view of the Cucamonga Valley would have shown a quilt of vineyard squares, striped with green rows of crops. Today, it’s a series of tight gray rectangular buildings, with swirls of eerily symmetrical cul-de-sacs in planned communities.

Hidden within this modern tableau are shocks of Cucamonga’s agrarian past. Century-old vines creep behind an office building, across from a flashlight factory, underneath power lines.

A small group of locals, led by Galleano, has made it their life’s work to preserve the Cucamonga Valley as a wine region. For decades their efforts looked futile. They witnessed many of the area’s most notable wineries reduced to the name of the shopping center or housing development that replaced it: Thomas Winery Plaza, Virginia Dare Winery Business Centre, Winery Estate Marketplace.

But now, Cucamonga wine’s true believers have reason for hope. A shift in the approach of the city government, the reclamation of hidden grapevines in a municipal park and the surging curiosity of outside winemakers have ignited a movement to save Cucamonga’s vineyards.

At stake is not just a few old vines but a place’s local color. In the case of Cucamonga, that color is the deep ruby hue of Zinfandel.

Galleano’s vineyard crew picks Zinfandel grapes at Lopez Ranch last August. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

A land of grapes

If Cucamonga wine turns out to have a savior, it will be Galleano, a quiet man in a Carhartt T-shirt and a “Corks Are for Quitters” trucker hat. Not only is he the owner and winemaker of the last commercial winery here, but he’s also responsible for tending to nearly all the remaining vineyards, including those owned or leased by others. Of the 450 acres of vines in the Cucamonga Valley — which spreads beyond the borders of Rancho Cucamonga into cities such as Fontana, Jurupa Valley and Ontario — Galleano farms 400. But that’s a fraction of the 1,600 acres his family once farmed.

One recent casualty is the Gateway Vineyard, situated near the Ontario airport in front of an office park. “We farmed that vineyard for 30 years,” says Galleano, shaking his head ruefully as he drives by in his white Ford Raptor. Though it now resembles an overgrown lawn, Gateway contains 26 acres of Zinfandel planted just after Prohibition. Galleano’s father had a farming contract with its longtime owner, the Mormon church, until a developer bought the parcel with plans to build an extended-stay hotel. Galleano had to stop farming Gateway, but the developer never got around to building anything either. It’s languished, abandoned since 2019.

But against all odds, life has found a way.

“Those old Zinfandel vines, I’ve seen them ran over until they were flat, and the next year they pop back,” Galleano says. He dreams of regaining access to the vineyard, “because those vines are still really viable.”

Postal delivery planes take off from the Ontario International Airport near the remains of the old Guasti winery. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

Gateway is merely one in a series of vineyard disappearances that Galleano has seen in his 40 years. Each time residential, industrial or commercial development boxes out an old vineyard, he believes something special is lost. “They want to name themselves ‘grape blah blah blah,’” he says, pointing to the Thomas Winery Plaza, where the former site of a historic winery is now a coffee shop. “But then they’re the ones ripping out the vines.”

Galleano clings to a promise from Intex, the Lopez Ranch owner, that it will keep some of the property’s vines — at the very least, the ones underneath a series of power lines, which can’t be developed anyway.

But that’s a small comfort. “I look at raw land and think, we could plant that,” he says.

It’s as if there are two Cucamongas. There’s the neat, orderly one that everyone sees. Then there’s the hidden, wild Cucamonga, a land of grapes.

Left: Vintners Domenic Galleano, left, and Gino L. Filippi sample wines at Galleano Winery. Right: A photograph in the Galleano Winery tasting room shows an aerial view of the Cucamonga Valley in 1933, when vineyards blanketed the area. Photos by Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

‘The poster child of poor urban planning’

The main drag in Rancho Cucamonga today is packed with the likes of Vitamin Shoppe, Home Depot, Hobby Lobby and Chili’s. It looks like it could be any suburban town in America. But it was not so long ago that it looked like no other place in the country.

The Cucamonga Valley was once a wine paradise, the epicenter of California’s nascent wine industry. In the early 20th century, grapevines stretched across 45,000 acres, roughly as many as Napa Valley has today. It was home to what was likely the largest contiguous vineyard in the world at the time. Today, about 1% of that acreage remains.

The wine history begins in 1839, when California was a territory of Mexico and its governor issued a land grant to a soldier named Tiburcio Tapia. Though his plan was to run cattle, Tapia planted grapes, a smart investment at the time. Los Angeles, known as the City of Vines as well as the City of Angels, had a booming wine trade, with dozens of vineyards within its city limits. Ships would sail up the coast, delivering southern California wine to ports in Santa Barbara, Monterey and San Francisco.

The city of Rancho Cucamonga and its surrounding towns were once covered in vineyards, but today the area looks very different. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

Hofer Ranch seen in the winter of 1945, after the vines have been pruned. Courtesy of Paul B. Hofer III

Thanks to wind, vineyards here aren’t plagued by the mildew pressure that necessitates fungicides in many other parts of California. Cucamonga may look like a desert, but groundwater is plentiful. Despite the hot summer days, grapes ripen slowly and evenly, rarely succumbing to raisins.

The Hofer family was one of many lured to the area for agriculture, buying a ranch in 1882 that they would eventually expand to 960 acres. Once the Hofers learned they couldn’t grow the corn and wheat that they’d farmed in Iowa, they turned to grapes with obscure names such as Damascus Black, Red Malaga and Tokay. (They planted the now-massive Grenache in 1919.) “The very early settlers back in the rancho days, damn near every one of them had a vineyard,” says the homesteaders’ great-great-grandson Paul Hofer III, who at 78 looks the part of the genteel rancher with neatly parted salt-and-pepper hair and faded brown cowboy boots.

The nascent scene would reach its pinnacle under vintner Secondo Guasti, who arrived in Cucamonga in 1878 from Piedmont, Italy. “Guasti put Cucamonga on the map,” says Gino Filippi, whose family began growing grapes in Cucamonga in 1922.

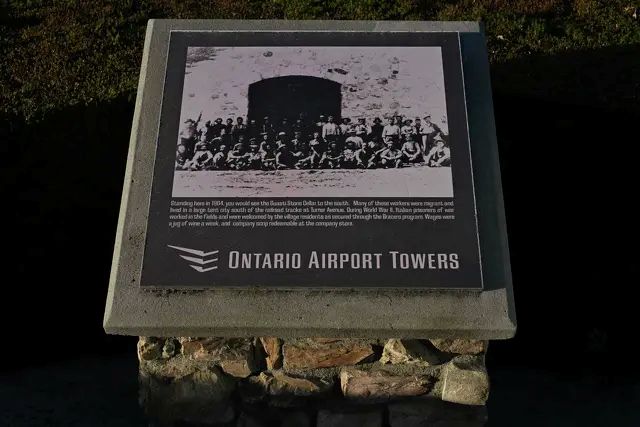

Guasti’s operation, the Italian Vineyard Co., ballooned to 5,000 acres. He planted Italian grapes like Nebbiolo alongside California standards such as Zinfandel, Mission and Palomino. He built a lavish villa for himself and massive stone cellars across the street from what’s now the Ontario International Airport.

Left: A Hofer family member knocks weeds on a horse-drawn cultivator, early 1900s. Right: Paul B. Hofer III’s father Paul Hofer II stands on a flatbed truck that contains picking boxes destined for the vineyards at harvesttime, late 1920s. Photos courtesy Paul B. Hofer III

Harvest at Hofer Ranch during World War II, when all of the pickers were women. The Army Air Corps claimed part of the ranch during the war to use as a training base. Courtesy of Paul B. Hofer III

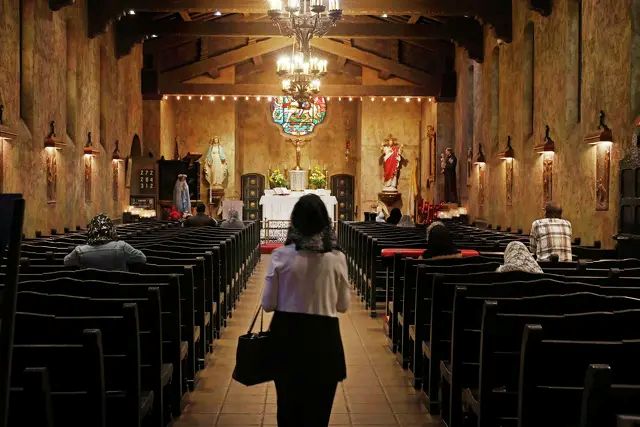

Guasti’s employees, including Filippi’s great-aunt and -uncle, lived in housing onsite and redeemed their wages at a company store. This self-contained world had a Catholic church, a blacksmith, a bakery, a hotel, a post office, a fire station. Workers laid tracks for a small mine train that would transport grapes throughout the valley. “It was a wine town, reminiscent of a village in Italy,” Filippi says.

The ruins of this civilization still stand. Moss and ivy blanket the stone cellars, segments of their roofs missing. Plastic wrap stretches tightly around a few scattered homes. The church remains active; Hofer, a member, tends to the grapevines that dot the perimeter of the parking lot. There’s a post office too, in a mobile trailer, that tells you where you are: Guasti, Calif.

The city of Ontario approached Galleano about restoring the stone wine cellars, but he couldn’t make it work. “It would have cost $100 million to renovate those 100-year-old buildings that haven’t been maintained,” he says. A developer owns the land and has said it is planning a multiuse site there that could involve hotels, restaurants and entertainment, but the timeline is unclear.

Prohibition took effect in 1920, forcing many California wineries out of business. But not in Cucamonga. The Volstead Act permitted citizens to produce up to 200 gallons of homemade wine per year, sending the demand for fresh grapes high. Cucamonga was ready to meet it: It sat near the nexus of the Santa Fe, Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads, as well as near an ice plant. Citrus growers had already been using the Pacific Fruit Express’ refrigerated railcars to ship their fruit nationwide; the grape growers hopped on too.

“Quite literally there were fortunes made during Prohibition selling grapes,” Hofer says.

Clockwise from top left: A plaque near the old Guasti winery, next to the Ontario Airport, commemorates its winemaking past. A bronze bust of founder Secondo Guasti (1859-1927) at the entrance to the San Secondo d’Asti Catholic Church. Parishioners enter the church before a morning service. A grape mosaic on the floor of the church, built by the Guasti family in 1926 as part of the Italian Vineyard Co. compound. Photos by Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

The façade of the Galleano Winery identifies its founding date as 1933, the year of repeal, but it in fact opened in 1927. To get through Prohibition, Galleano’s grandfather sold glass jugs of grape juice. “There would be a little tag on the top with instructions of how not to ferment your wine, because that would be illegal,” Galleano says. “‘Do not add yeast. Do not put it in a cellar. Do not rack it off.’”

The local wine scene took off after Prohibition, its winery count topping 60 in 1940. The peak wouldn’t last long.

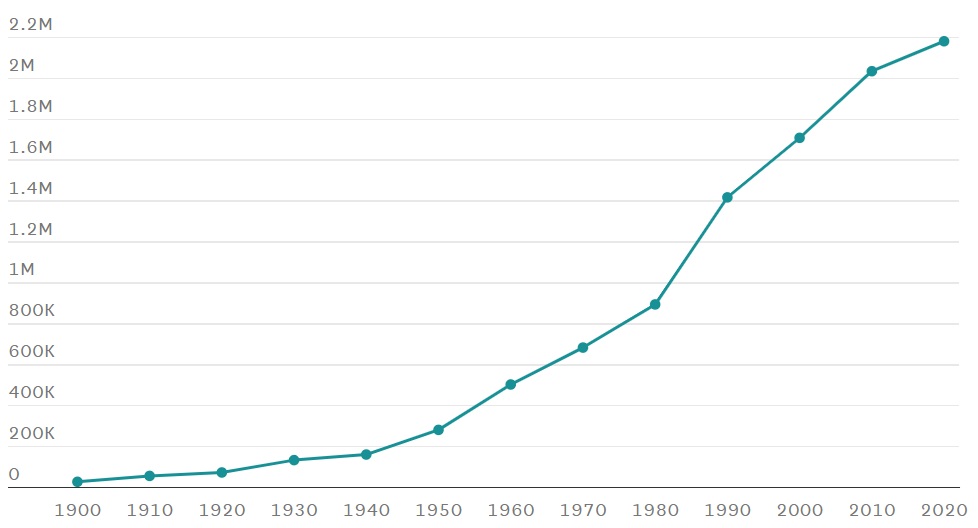

Southern California’s population boomed as soldiers returning from World War II settled here, and the defense industry saw in the Cucamonga Valley open land and moderate weather that would allow them to build year round. When the Kaiser Steel Plant began operating in Fontana in 1942, Galleano says, “that was really the beginning of the end.”

Urbanization roared. Interstate 15 came through in the ’70s, carving up Lopez Ranch. (It would later be carved up further by Interstate 210.) Angelenos spilled out into the Inland Empire; San Bernardino County’s population swelled by 213% from 1940 to 1960. A crash in the wine market in the ’50s sealed the fate of many winegrowers, who couldn’t afford not to sell their land. All but about 10 of the wineries closed.

Population of San Bernardino County

Source: Van Leuven, Andrew J

L. Dennis Michael, the mayor of Rancho Cucamonga, saw this firsthand growing up on a farm in town. His father initially refused several offers for the family citrus grove, but he couldn’t hang on forever. “Water prices got so high, the property taxes were pretty high and there were speculators for land,” Michael says. His family farm, along with many others, “all turned primarily to housing.”

When the Ontario airport expanded in the late 1950s, it claimed eminent domain to seize a large chunk of the Hofer Ranch, including some of its vineyards. The Hofer family fought it for seven years in court but lost. Of the roughly 920 grape acres that Hofer estimates the ranch held at its apex, 10 remain today.

Left: Paul Hofer, Sr. on the first engine tractor at Hofer Ranch in 1923, used in conjunction with horses. Because of its steel tires, the tractor was difficult to steer, so the driver had to stand up for leverage. (Courtesy Paul B. Hofer III) Top right: Fifth-generation rancher Paul Hofer III at Hofer Ranch, located next to the Ontario Airport. (Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle) Bottom right: Pepe, a Galleano Winery crew member, carries Palomino grapes during a harvest at Lopez Ranch. (Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle)

Left: Paul Hofer, Sr. on the first engine tractor at Hofer Ranch in 1923, used in conjunction with horses. Because of its steel tires, the tractor was difficult to steer, so the driver had to stand up for leverage. (Courtesy Paul B. Hofer III) Top right: Fifth-generation rancher Paul Hofer III at Hofer Ranch, located next to the Ontario Airport. (Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle) Bottom right: Pepe, a Galleano Winery crew member, carries Palomino grapes during a harvest at Lopez Ranch. (Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle)

Gino L. Filippi stands near the fenced-off remains of the old Guasti winery. Filippi’s great-grandfather Giovanni, born in 1870, came to America from Veneto, Italy and was one of the Italian masons who built the Italian Vineyard Co. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

The same story was unfolding nearly everywhere in mid-century America. Open land yielded to new roads, new industries and new families fleeing inner cities. In response, there was suddenly a rush to enact land-use restrictions like the 1965 Williamson Act, which allowed California cities to provide tax incentives for keeping land in agriculture or open space. Napa Valley passed its groundbreaking Agricultural Preserve in 1968, the first of its kind in the nation, without which St. Helena’s vineyard-swollen hillsides might today house a shopping center.

In Cucamonga, by contrast, development proceeded unconstrained. “It’s like the poster child of poor urban planning,” says Dave Potter, owner of Santa Barbara’s Municipal Winemakers and a Rancho Cucamonga native. “Growing up, there didn’t used to be a Home Depot every 10 miles. There’s no city center now, it’s just strip malls.”

By the time winemaker Mikey Giugni was growing up in Rancho Cucamonga in the ’90s, he says residents regarded the area’s vineyards as an unremarkable quirk of the landscape, if they realized they existed at all. In 1995, the federal government approved Filippi’s petition to create the Cucamonga Valley American Viticultural Area. There were only three wineries by then; even Filippi’s own father, a Cucamonga vintner his whole life, considered the petition a waste of time.

The key industry in the Cucamonga Valley today is logistics — a modern distortion, perhaps, of the railroad network that kept it in business during Prohibition. Ontario is home to UPS’ West Coast hub and Amazon’s largest U.S. warehouse, which can hold up to 50 million items.

“Cucamonga is this interface of where agriculture and population density have clashed,” Giugni says. “Population density is winning.”

Warehouses and delivery truck containers bustle near the vineyards of Galleano Winery. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

A cool-kids destination

Despite Cucamonga’s dwindling vineyards, the reputation of its wines has grown.

Sonoma County winemaker Carol Shelton began buying Lopez Ranch Zinfandel in 2000, at considerable expense. Transporting the refrigerated grapes to Santa Rosa costs her $4,000 in freight costs alone. Apart from a few short-lived projects, Shelton was the only outsider making Cucamonga wine for almost two decades.

Then a slew of new-wave winemakers began discovering Cucamonga, thanks in part to a 2014 Chronicle article in which Jon Bonné described the region as haunted by “ghosts of wineries now gone.” Inspired by the story, winemaker Abe Schoener moved from Napa to Los Angeles and started a new wine brand, Los Angeles River Wine Co., with the express purpose of working with the Cucamonga vineyards. Others, including Osborne of A Tribute to Grace, came down to see the vineyards and ended up buying fruit from Galleano and Hofer.

The reigning grape in Cucamonga is Zinfandel, but there’s also quite a bit of Palomino, a white variety that’s the traditional base for Sherry in Spain. It’s no wonder, then, that Cucamonga’s wineries — especially Galleano Winery — have always specialized in Sherry- and Port-style fortified wines. A tiny vineyard, which Galleano calls Francis Road and Schoener has dubbed “Maglite,” for the adjacent flashlight factory, has old Grenache and Mission vines. The Galleano home ranch is populated by grapes including Mataro (a synonym for Mourvedre), San Salvador and Alicante Bouschet — the latter two teinturiers, a rare type of red-fleshed grape.

Winemaker Abe Schoener, far right, watches Galleano crew members harvest Palomino grapes from Lopez Ranch for his Los Angeles River Wine Co. last August. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

Left:Winemaker Carol Shelton, seen in Geyserville in 2004, was the only outside winemaker buying Cucamonga Valley grapes consistently for almost 20 years. She is committed to making the wine, even though it costs her $4,000 in freight costs alone to get the grapes. (Craig Lee/S.F. Chronicle) Top right: Raj Parr, a high-profile California winemaker seen here in 2023, calls his 2023 Alicante Bouschet from the Galleano vineyard one of the best wines he’s ever made. (Jessica Christian/S.F. Chronicle) Bottom right: Wine samples in the lab at Galleano Winery, which specializes in hearty Zinfandel blends and fortified Port- and Sherry-style wines. (Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle)

Left:Winemaker Carol Shelton, seen in Geyserville in 2004, was the only outside winemaker buying Cucamonga Valley grapes consistently for almost 20 years. She is committed to making the wine, even though it costs her $4,000 in freight costs alone to get the grapes. (Craig Lee/S.F. Chronicle) Top right: Raj Parr, a high-profile California winemaker seen here in 2023, calls his 2023 Alicante Bouschet from the Galleano vineyard one of the best wines he’s ever made. (Jessica Christian/S.F. Chronicle) Bottom right: Wine samples in the lab at Galleano Winery, which specializes in hearty Zinfandel blends and fortified Port- and Sherry-style wines. (Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle)

“All of it just feels wild,” Shelton says. In the wine she makes, “I get pomegranate, dried cherries, dried cranberries and all these different layers of dry, deserty spices,” like cardamom, cumin and coriander.

Raj Parr, who works in Cambria but created the Scythian brand just for his Cucamonga wines, calls the 2023 Alicante Bouschet from the Galleano vineyard one of the best wines he’s ever made.

These outside winemakers seem to be rubbing off on Galleano.

His family winery, located next to a Sam’s Club in Jurupa Valley, looks lost in time. Galleano ages his wine in the same tall redwood tanks that his family has used since the late ’40s and early ’50s — vessels that were common in California and have all but vanished today. The only barrels in the place are crusty and black, containing a solera-style Sherry that dates back to 1968. The bottles in the tasting room boast names such as Chianti, Mellow Burgundy and California Champagne. Those geographically protected terms are illegal to use now, but Galleano Winery was grandfathered in.

Still, there’s a whiff of something new and modern. Emerging from the musky cellar to the crush pad outdoors, Galleano opens the valve of a stainless-steel tank, and out pours a pale yellow liquid. “This is the first time I made a white wine from Palomino,” he says proudly, as opposed to a fortified style. It’s crisp, clean, bright. From the neighboring tank, he extracts a fuchsia-hued sample of what he’s calling white Zinfandel, from Lopez. It’s Galleano’s first foray into dry rosé.

Domenic Galleano holds a white wine sample on the crushpad at Galleano Winery, with his daughter Esme Galleano, 2. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

A secret vineyard

On an 80-degree May morning under clear blue skies, Gino Filippi treads across flattened buckwheat in Rancho Cucamonga’s Central Park. He shows off a large vine hiding behind a bush. It looks healthy and green, with vigorous leaves shooting out in all directions. That’s the result of a careful rehabilitation, now that the city has given Galleano a lease to 9 acres of this public space.

Central Park is where the past and future of this region’s wine identity converge. Within the 30-acre expanse, where the city envisions eventual running trails, an amphitheater, tennis courts and playgrounds, a secret vineyard was hiding.

Galleano and Filippi knew there were some vines at Central Park but had no idea how many were obscured beneath the unruly tangles of buckwheat. And they didn’t know the city might be interested in revitalizing them until officials called last year and asked for help.

Galleano, Filippi and friends painstakingly cut away the 3-foot-tall stands of buckwheat, careful not to uproot any vines. They revealed 60 scattered Zinfandel, Rose of Peru and Mission vines, probably planted from 1913 to 1915. The vintners treated them with the delicacy of an archaeologist at a dig. Noticing that squirrels and rabbits were eating new vine shoots, Filippi erected small cages around some of the plants. He and Galleano gently prune and hand-water each one as if it were a house plant.

These vines, and hundreds of new ones that Galleano is planting, will become the focal point of Central Park’s Viticulture Pavilion, surrounded by a café, patio and terraced steps. Galleano has persuaded the city to add an educational center where people, especially kids, can learn about grape-growing and the city’s heritage.

“It’s important to the city,” economic development manager Tanya Spiegel says as she follows Filippi around the Central Park vines. “You see other communities around the state where they’ve communicated their wine history better, like Sonoma.”

In 2022, Rancho Cucamonga approved an Agricultural Overlay, a new zoning plan designed to encourage land that was historically agricultural to remain so. Filippi wishes it had been around a few years earlier, when the developer tried to convert that 100-year-old Zinfandel vineyard into extended-stay hotels. “It was too late to save Gateway,” he says.

But that hasn’t diminished his feeling of excitement. “There’s some really encouraging things happening — granted, on a small scale,” Filippi says.

Domenic Galleano walks through Central Park in Rancho Cucamonga. He now has a lease to care for the long-abandoned vines that were hiding in the park. Erik Castro/For the S.F. Chronicle

His own family’s winery is entering a new chapter too. The Filippis recently got out of their lease for the Joseph Filippi Winery, which is on city-owned land. The city gave the lease to an affordable housing developer who might have closed the winery entirely. But the city of Rancho Cucamonga is requiring the developer to make wine at the site.

While Mayor Michael doesn’t foresee wine becoming a significant economic force for the city, he says he thinks that projects such as Central Park and a preserved Filippi Winery can add an intangible spark of excitement. He envisions a boutique hotel and spa, and maybe a restaurant, alongside the winery eventually.

There will be no hotel or spa at Hofer Ranch, but a revitalization is underway there too. On the banks of an arroyo that bisects the property, near the Grenache vines that Hofer describes as “survivors,” he wants to plant a new vineyard. Disease wiped out a recent attempt to introduce Palomino, Pedro Ximénez and Golden Chasselas, three old-fashioned varieties that would seem relegated to the California history books.

But Hofer is determined to try again. “I’ll stop at nothing to see if we can get another vineyard here,” he says, gesturing through the window of his grandparents’ house, past the palm trees and toward the arroyo. His grandparents have been dead for decades, but their home has been preserved as if it were a museum. A candlestick telephone, with separate ear- and mouthpieces, still hangs on the wall.

The whole enterprise of Cucamonga wine, in fact, can at times feel like a museum, a scattering of artifacts that have improbably survived into an epoch where they don’t belong. Yet the vineyards, like the true believers who steward them, are undeniably alive. They are the keepers of the records, witnesses to every boom and bust this region has seen in the past century. As long as any of them keep bearing fruit, Cucamonga’s past will never die.