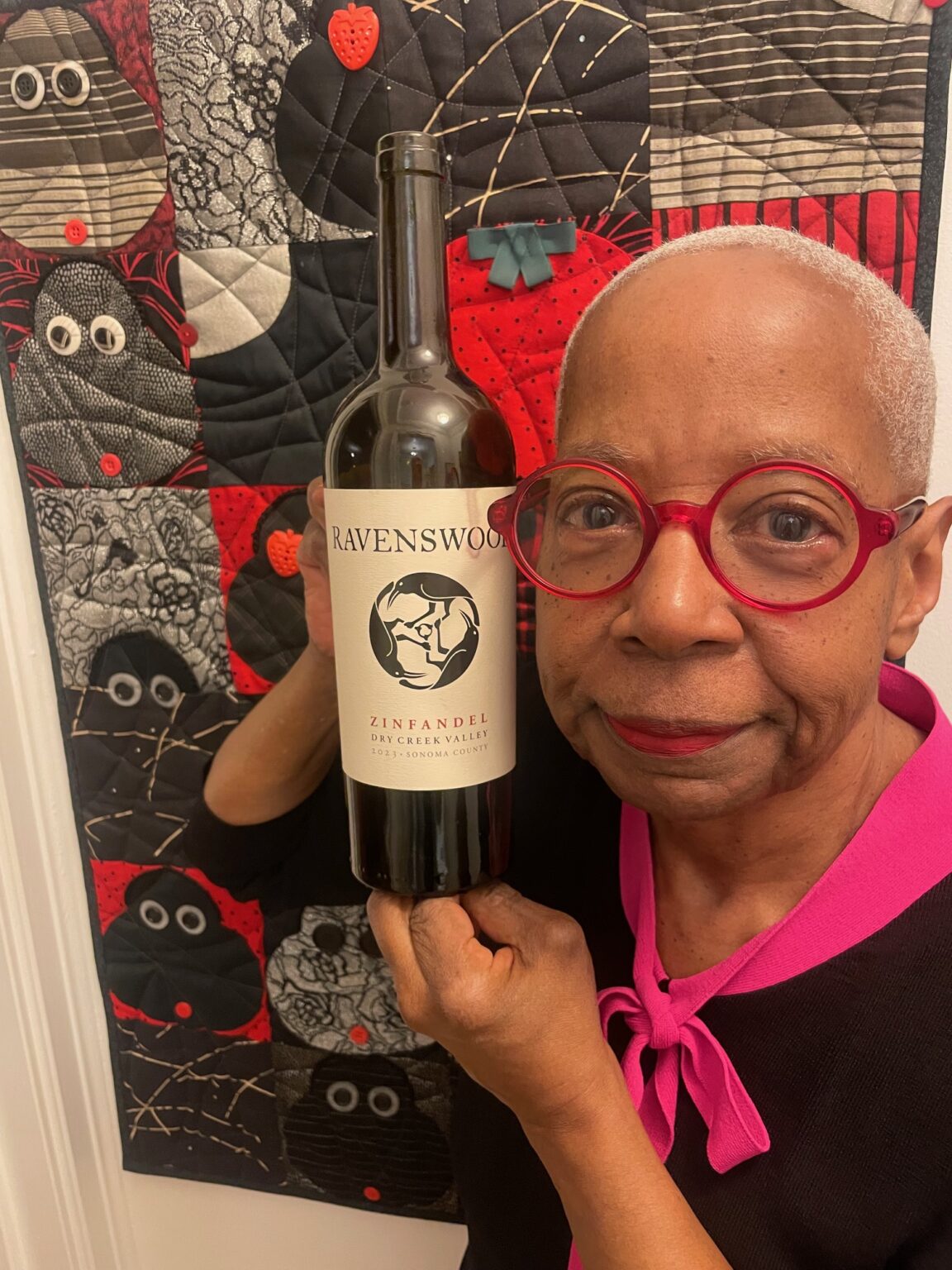

Ravenswood Zinfandel is back! And if you’re wondering if the new owners honor the old owner-winemaker, there is a tiny hint on the back label that might provide a clue.

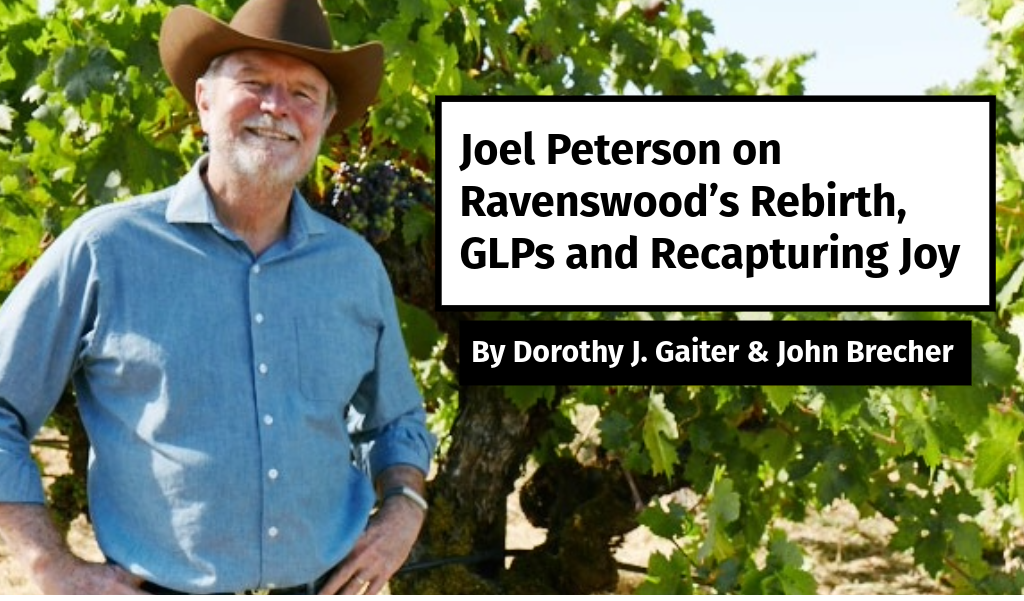

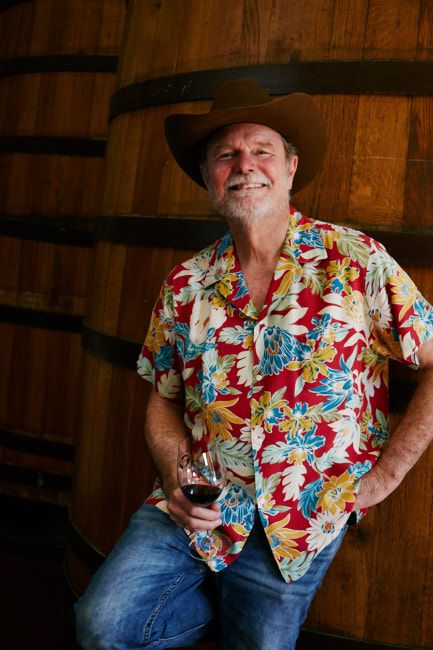

A half-century ago next year, Joel Peterson founded Ravenswood in Sonoma and proved what a great wine Zinfandel could be. Now 78, he became an icon. In the meantime, Ravenswood went public; was bought by giant Constellation; and then got dumped by Constellation to Gallo, which didn’t know what to do with the brand, so it remained in limbo for years. Meantime, Peterson founded a new small winery, Once & Future, to recapture the magic of Zinfandel, and his son, Morgan Twain-Peterson, became a Master of Wine with his own highly regarded winery, Bedrock Wine Co. Morgan’s son, Joel, recently made his first Zinfandel. He’s 5.

Now, Gallo has resurrected Ravenswood as a fine Zinfandel. The initial production, the 2023, is about 6,000 cases and Gallo has hired Peterson as “spirit guide,” he told us.

We can’t imagine many people who have lived the sweep of American wine more broadly than Peterson, who grew up in California with wine-passionate parents, so we gave him a call to talk about where we are and where we are going.

Joel Peterson

Where are we?

Peterson said there were 345 wineries in California when he started Ravenswood and now there are 4,684 and about 10,000 in the U.S. “So there is a huge increase in labels and in images and in people making wine and in big corporate wines…So we’ve grown and grown and grown, and in that growth, we always had these kind of boom and bust cycles with over-planting and over-wine-production. It was just a cyclical thing. It just happened all the time. But in that time, there was always growth in wine consumption. So you had things like ‘60 Minutes’ and wine’s good for you [the French Paradox]. We had the ’76 tasting [Judgment of Paris]. There was always some good news that drove the larger cultural understanding of wine that allowed wine to grow… We are at one of those glut cycles now. It seems a little different because the category of wine is not growing; it is actually shrinking. So the consequences of this overproduction now are far more obvious than the consequences in the past. Now whole vineyards went unpicked this year. You’ve seen people pulling up grapes in favor of putting in almonds or bushes or pomegranates.”

Why is wine slumping?

Peterson mentioned several negative trends:

–“There’s kind of a strong neo-prohibition going on, that no amount of alcohol is good for you.”

— “There are hundreds of labels for consumers to sort through and wine has gotten expensive. And there’s a homogeneity of wines and a sameness that has become pervasive, particularly in supermarkets, in part because those wines are frequently made by large organizations that are making them all from the same place rather than individual places.”

–“And then there’s my favorite new drug, the GLP-1 drugs, which basically suppress your desire for food and drink and really suppress your desire for joy. So ultimately there’s less socialization with friends, food and wine because people are not interested in that at this particular juncture because of the drug they’re taking.”

–“The wine business damaged its own reputation over the years with things like natural wines, which implies that all other wines are unnatural. And clean wines — makes it seem like there’s thousands of additives put in wine. Yes, there are legal additives you can add to wine, but most people don’t use them at all. And no-sugar wines — really? Most red wines don’t have sugar anyway, so it’s like there’s this kind of marketing push, which has, I think, dinged wine as a whole and made it look like a negative beverage as opposed to the healthy beverage that it in fact is.”

–“And at least here in the U.S. we’ve kind of hollowed out the middle class, which was really one of the sources for wine growth. The middle class owns less wealth than the top 1% at this point, and I don’t think there are enough people in the top 1% to focus your entire marketing efforts towards them.”

What happened to the joy?

“I think the joy got corporatized and complicated. I don’t know exactly how to describe this, but people began to think of wine as a complicated beverage and an expensive hobby… The reason that my parents got interested in wine was because there was a sense of discovery. You discovered new worlds in every bottle. You discovered places you could go and people you could meet who were interesting in their own right. That was different than your day-to-day life. And you could incorporate it into your day-to-day life in ways that were flavorful and meaningful and just made it more interesting. I think we’ve just lost some of that.”

Dottie with Ravenswood Zinfandel

What do you do at Ravenswood?

Peterson says he does some events for Gallo, advises on the label (he calls the original design “the most tattooed logo in the wine business”) and takes part in tastings. “I haven’t been involved in the winemaking other than I taste with the winemaking crew. They’ve got a wonderful group led by a guy named Michael Eddy-Cort, and it’s like four people that are dedicated to this. When I taste with them, they said this is the most fun we’ve ever had making wine… I’m on the periphery, but I’m also integrated. And I’ve been told that if there’s something that troubles me, I should speak up and let them know what it is and they will adjust.”

So, about those tiny initials on the back label, PFM. What do they mean?

Peterson told us that when he was meeting with Gallo to discuss the relaunch of Ravenswood, they asked about the history. “So I tell the story about the first encounter with ravens on my first harvest and how I managed to pick up all the grapes myself, which was four tons. It was supposed to rain on me and it didn’t rain — and didn’t rain, in my mind, because these two huge ravens floated into the vineyard and sang to me while I was loading the grapes. And I got the grapes down to Joe Swan’s winery [in the Russian River Valley] and as we dumped the last box in the crusher, the skies opened up and it poured. It was PFM — pure fucking magic. They picked up on the PFM, and so they said, we’re going to put this on the label.”

So where do we go from here with wine? Gallo and other large producers get a lot of grief, but Gallo is doing some good things with smaller wineries, like Massican, and there are also some major players, like Jackson Family, that are producing fine, highly personal wines. Is that part of the hope for the future?

“The answer is yes, absolutely. Gallo is kind of a different cat than a lot of the other giants. Obviously, it’s the most gigantic of the gigantic, but it’s still a family-owned business and they still run it in that way. I don’t think that people like Constellation or Treasury or others that are traded in the public markets will be the salvation of the wine business. They’re too driven by quarterly reports and they make decisions based not on what’s best for the wine business, but what seems to be best for their business. And frequently that isn’t what’s best for the wine business. So my guess is that it won’t come from that direction. It might come from the Gallo direction. They’ve been around for a very long time and have weathered many changes and have been really adept at flexing and changing to meet the needs of whatever the consumer population is.”

When you founded Ravenswood in ’76, wine was still not that popular in America, but you made it into an iconic brand. What lessons from then could be helpful to the industry today?

“Part of the answer is that wine wasn’t that popular, but there was a core of people who were really interested in it. There were lots of people who were kind of the yuppies of their time, if you will, that were interested in wine. They got interested in it because it was good, it was authentic, it was interesting, and it turned out to be good fun. And I think that a lot of that fun has gone out of it. With the corporate interests involved, it’s become more about sales — make up a story. So more authenticity is going to be important. I really think the wine business is still a people-to-people business, and we’ve lost some of that. But ultimately, I think a lot of the hope resides with smaller producers who live the life and walk the walk and are really authentic. They’re people who can connect with other people and interest people in the art and the culture of winemaking, which I think has been lost in many ways.”

Once & Future with short ribs

Once & Future with short ribs

So, on the whole, are you optimistic?

“I’d say cautiously optimistic because I think that people ultimately want joy in their lives. And if we ever get to a point where income is rebalanced in some way or shape, shape or form, people will want wine, want that experience, want that socialization associated with it. And I do think wine will come back into balance again and what we’ll be left with will be higher quality and more interesting wines. Those will be the survivors…

“But this still is going to have to appeal to a younger generation… I’m fortunate enough to work with Morgan and Morgan has a group of winemakers who work with him who all have their own group of winemakers, and they’re all under 40, most of them are under 30, and they are energetic advocates for wine, and they make good wine as well. So it’s going to take a combination of people like that and perhaps people who have a bit more financial capacity to figure out how to make wine appeal to the next group of wine buyers without cheapening it, without losing its integrity.”

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal’s wine column, “Tastings,” from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart’s show, and as the creators of the annual, international “Open That Bottle Night” celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.